Berkley

Published October 25, 2016

ISBN-10: 0451474635

ISBN-13: 9780451474636

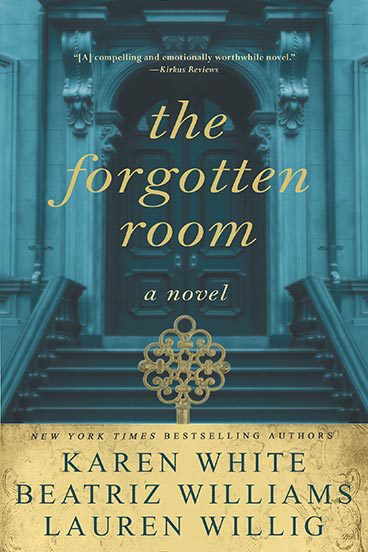

The Forgotten Room

By Karen White, Beatriz Williams, and Lauren Willig

Available Now in Paperback

Buy the Book

eBOOK

AUDIOBOOK

Support Your Southern Independent Bookstore!

Karen White is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate program designed to provide a means for sites to earn fees from qualifying purchases at Amazon.com.

Pictured from left, New York Times Bestselling Authors Karen White, Beatriz Williams, and Lauren Willig.

New York Times bestselling authors Karen White, Beatriz Williams, and Lauren Willig present a masterful collaboration—a rich, multigenerational novel of love and loss that spans half a century….

1945: When the critically wounded Captain Cooper Ravenal is brought to a private hospital on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, young Dr. Kate Schuyler is drawn into a complex mystery that connects three generations of women in her family to a single extraordinary room in a Gilded Age mansion.

Who is the woman in Captain Ravenel’s portrait miniature who looks so much like Kate? And why is she wearing the ruby pendant handed down to Kate by her mother? In their pursuit of answers, they find themselves drawn into the turbulent stories of Gilded Age Olive Van Alen, driven from riches to rags, who hired out as a servant in the very house her father designed, and Jazz Age Lucy Young, who came from Brooklyn to Manhattan in pursuit of the father she had never known. But are Kate and Cooper ready for the secrets that will be revealed in the Forgotten Room?

The Forgotten Room, set in alternating time periods, is a sumptuous feast of a novel brought to vivid life by three brilliant storytellers.

“Engaging, complex characters and an intriguingly twisty plot of false leads will help readers justify a weekend spent reading, without interruption please! An excellent suggestion for fans of historical fiction, mysteries, and family relationships, all with a hint of romance.”

—Library Journal, Starred Review

“Strong female characters, swoon-worthy romance, and red herrings abound in this marvelous blend of romance, historical fiction and family saga.”

“Strong female characters, swoon-worthy romance, and red herrings abound in this marvelous blend of romance, historical fiction and family saga.”

“…the authors do a wonderful job of slowly teasing out the details while keeping the different story lines moving along.”

—Booklist

“…a compelling and emotionally worthwhile novel.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“Readers will be utterly enthralled…Spanning a century and three lives, this sumptuous, suspenseful and heart-wrenching story will keep you up all night.”

—RT Book Reviews TOP PICK

Chapter 1

New York City

June 1944

Kate

The patter of rain against the blacked-out stained glass dome above where I sat numbed me like a hypnotist’s gold watch. Neither the hard marble step beneath me nor the delicately carved staircase spindle pressed against my forehead was enough to override the lullaby effect of the raindrops. I tried to focus on the ornate staircase of the old mansion, to study the fine architectural details of the structure that even the conversion into a hospital couldn’t mask.

I recalled the walks I took as a child down Sixty-ninth Street with my mother, walks that weren’t convenient to our neighborhood but instead appeared to be a destination rather than a happenstance. We’d cross the road and pause, looking up at the seven-story stone mansion, the elongated windows staring blankly out at us, seemingly as curious as I was about why we were there. My mother had once told me that she’d lived there briefly when the building had been a boardinghouse for respectable women. But she’d never mentioned why she felt compelled to return to the spot across the street again and again, until her death three years before. It had seemed almost serendipitous when I had accepted the position at Stornaway Hospital following medical school, almost as if my mother had planned it all along.

My gaze settled on the far wall, on a bas-relief depicting a recurring motif of Saint George slaying the dragon, which I’d noticed throughout the building since I’d begun working at the hospital nearly a year before. My eyelids fluttered closed for a moment, watching the scene against the dark backdrop of my lids, imagining I could see the saint and the dragon stepping from the wall and writhing on the tiled floor in their perpetual battle.

I forced my eyes open, if only to assure myself that the stone adversaries were still stationary. Holding on to the banister, I pulled myself to a stand. I was so very, very tired. It was my second double shift in a row, and I doubted it would be my last. The city’s hospitals were being flooded with the arrival of wounded soldiers from the recent invasion of the French coast. With our ranks already spread thin by doctors enlisting and heading overseas, those remaining were working hours rarely seen past medical school.

The blare of an approaching siren helped me to stand up straighter, to compose myself before any of the nurses could find me in such mental disarray. As the only female doctor on staff, it was hard enough maintaining the persona of a woman with no feelings or personal needs in front of the male doctors. It was nearly impossible in front of the nurses. If they’d asked me why I’d become I doctor, I would have told them. But they didn’t ask. They seemed to be of a like mind when it came to me—I was a doctor because I thought I was too good to be a nurse.

There were a few who were deferential to my status of doctor regardless of my gender, but the rest were too traditional, having worked hard to come up the ranks in nursing, to consider me to be any more than an upstart.

I almost laughed at the thought, recalling all the bedpans I’d changed and sutures I’d sewn due to the abysmal shortage of health-care workers. But the laugh died in my throat when I realized the siren was getting louder, as if it was headed in my direction. I inwardly cursed the blackout curtains and painted windows that obscured all views from inside the hospital with the same effectiveness as blacking out the city’s skyline from potential attackers.

Fully awake now, I ran down the spiral staircase, past elegant rooms retrofitted into surgical theaters, a laboratory, and a convalescents’ dormitory brimming at full capacity, my white coat flapping against my bare legs. It had been years since I’d had a good pair of nylons, but I’d seen too much of war to mourn their absence.

I was the first one to reach the foyer, grabbing a flashlight on the hall table and flipping it on. The inner doors to the vestibule were temporarily affixed to the wall, requiring only a swift pull on the outer doors to access the outside. A strong gust of rain knocked into me, effectively soaking me and plastering my coat and dress to my body.

I ran down the slippery stone steps toward the ambulance as it pulled to the curb, its headlights with the top half painted black, its flashing lights extinguished. The driver, a large man with sad eyes peering out from beneath the brim of his dripping hat, stepped out of the ambulance.

“Wait,” I said, blocking his path, having to shout to be heard over the din of the rain as it hammered the ambulance and streets. “We have no more room. We even have patients on cots in the dining room. We are beyond capacity.”

“Just following orders, ma’am. We got an officer here right off the boat who’s in pretty bad shape. They told me to bring him here.”

“But . . .”

The man walked past me as if I were a small yipping dog just as Dr. Howard Greeley walked calmly down the stairs with an umbrella and approached the back of the ambulance. His bug eyes raked over me, taking in my sodden appearance and clothes, which had melded to my body. He didn’t offer shelter under his umbrella.

With a quick shake of disapproval, he turned to the driver. “What do we have here?”

“Officer, sir. He’s in bad shape.”

“We’ll find room for him.” Dr. Greeley sent me a withering look.

Both men continued to ignore me as the ambulance doors were thrown open by an orderly, allowing us to peer inside to where a form lay huddled beneath a blanket. Despite the June heat, the body twitched as if seized by chills.

As the orderlies began to prepare the patient, Dr. Greeley was handed a folder that I assumed was the patient’s medical records. No longer willing to be a bystander, I grabbed the folder, then moved to stand under the doctor’s umbrella. Ignoring his scowl, I said, “Good idea. You hold the umbrella while I look at this.”

Trying not to drip onto the pages, I skimmed the notes inside, paraphrasing for Dr. Greeley. “He sustained a bullet wound to his leg at Cherbourg—damage to the bone. Field doctor wanted to amputate, but”—my gaze drifted to the top of the page where the soldier’s name was printed—“Captain Ravenel talked them out of it. They debrided the wound and applied a topical sulfanilamide, but lack of time prohibited delaying primary closure.” I felt my lips tighten over my teeth, understanding now how the wound had become infected. “The apparent effectiveness of the sulfanilamide led them to the conclusion that he was well enough to be stitched up and put on a ship home, seeing as how his leg, assuming it recovers, won’t be much use to an infantryman.”

I held the flashlight higher as I scanned down to the last paragraph, written in another hand and presumably by the ship’s surgeon. “A piece of bone fragment or another foreign body must still be lodged in the leg, causing the infection, but because of a scarcity of penicillin on the ship, the captain said he’d wait for surgery until he got stateside.” I closed the folder. Fool, I thought, but with a tinge of admiration. “You’re a real hero, Captain Ravenel,” I said softly.

The orderlies began removing the stretcher from the ambulance, eliciting a groan from its inhabitant. The exposed part of the blanket quickly darkened to a muddy brown from the rain, and rather than wrest the umbrella from Dr. Greeley, I thrust the folder and flashlight at him before shedding my white coat, determined to shield the soldier from any further harm.

As the orderlies carried the stretcher up the steps toward the door, I did my best to block the patient from the teeming rain, succeeding only marginally due to the saturated nature of my coat. I couldn’t see his face, but I leaned down to where it would be positioned on the stretcher and spoke to him. “Captain Ravenel, I am Dr. Kate Schuyler and you’re at Stornaway Hospital in New York City. We are going to take very good care of you.”

It was my standard refrain to each and every patient who came through the elegant brass and wrought-iron doors, but for some reason it seemed this soldier needed to hear those words more than most.

Two nurses held the doors as the orderlies brought in the stretcher, then looked at Dr. Greeley for instructions. “Take him to surgical theater one. It’s the only remaining bed we have. We’ll need to examine him first, of course, but my bet is we’re going to have to take off his leg.”

“No.”

We looked at each other in surprise, wondering where the seemingly disembodied voice had come from.

“No,” the voice came again, yet this time it was accompanied by a firm grip on my wrist, the fingers strong and warm.

For the first time, I looked down into the face of Captain Ravenel, and the air between us stilled. He was the most beautiful man I’d ever seen, with eyes the color of winter grass illuminated under fine dark brows and straight black hair. His skin, though drawn and pale around his mouth, was deeply tanned.

But it wasn’t even his looks that made it impossible for me to glance away. It was the way he was looking at me. As if he knew me.

“Don’t let them take my leg,” he said, speaking only to me. Sweat beaded his forehead and the chills continued, yet his plea did not seem to come from delirium. “Please,” he added softly, his eyes boring into mine. Then his grip slipped from my wrist until his arm lay useless at his side, his eyes closed.

“Operating room one, please,” Dr. Greeley repeated as if he hadn’t heard the man’s plea.

A nurse led the way toward the small elevator.

“No,” I said, as surprised as everyone else that I’d said the word aloud. I faced Dr. Greeley. “We should clear up any infection before we can operate, and that can take days. He can have my room.”

Because of my long hours at the hospital, I’d been given an attic room on the seventh floor of the building. It had been meant to be temporary, but when my apartment lease had come due, I’d allowed it to expire, realizing that I was wasting rent money by rarely sleeping there. I had no remaining family, and it seemed almost natural to move into the top room, where I could pretend, if just for a little while, that this was my home and that I had family in the rooms below.

The room itself was in what was currently used as a storeroom. But with its domed skylight and rows of tall, fanned windows, I imagined that the room had once had a much more glamorous existence.

“That’s hardly appropriate,” Dr. Greeley said, looking affronted, as if he’d never made inappropriate suggestions to me.

“I’ll move into the overnight nurses’ room. Even if I have to sleep on blankets on the floor—it’s just for a little while.”

He frowned. “I can’t be running up and down those stairs all day to see to him. He’ll be much better off in the operating room.”

“Then I will,” I said, sensing the restlessness of the stretcher-bearers as they waited. I wasn’t sure why I was fighting so hard for this man I didn’t even know. But I remembered his eyes, and the feel of his fingers on my bare skin. Remembered the way he seemed to recognize me.

“After we examine him and begin treatment, we will set him up in my room and I will be responsible for his care. And if I cannot clear up the infection and his leg needs to be amputated, then you will have my full support.”

Slightly mollified and delighted to have the opportunity to watch me fail, Dr. Greeley gave a curt nod. “Fine. Let’s take him to the operating room to examine him, and if all looks well we’ll move him to the top of the building. Just know that he is your full responsibility along with all of your other duties. It would be a shame if his condition worsens because you are not up to the task.”

“I won’t shirk my duties,” I said, wondering at my vehemence. I looked down at the officer again, surprised to find his eyes open. But they were glazed, and even though he was looking at me, I wasn’t sure he was seeing me.

“Victorine,” he said softly before his eyelids slowly fluttered closed.

I watched as the stretcher disappeared into the elevator, feeling suddenly bereft.

Chapter 2

December 1892

Olive

On the night Olive Van Alan discovered what lay at the top of the mansion on East Sixty-ninth Street, she was planning a different kind of mischief altogether. But that was how these things happened, wasn’t it? You were always too busy looking in the wrong direction.

So there Olive lay in her narrow bed, turning over her plans, as blind as a mole in the darkened room. If she felt any foreboding at all, it was focused on the housekeeper, who was making her usual final inspection down the corridor—petticoats rustling starchily against her rumored legs, knuckles rapping against the doors, each crisp Good night, Mona and Good night, Ellen followed by the automatic Good night, Mrs. Keane—before she locked the vestibule behind her.

The lock, Olive had been told, was for her own protection. Mrs. Keane came from England—apparently it was a prestigious thing, in these circles, to have an English housekeeper—and she had explained, in her voice like the cracking of eggs, that the girls were not being locked in, goodness no, but rather the outside world and particularly its base male appetites locked out.

Olive, as she went about her daily business, encountering males in every corner, had wondered where these base appetites were hidden, and why their owners could not be expected to control them without the support of a stout Yale deadbolt lock—apparently these were nocturnal appetites, as well as base—but she hadn’t dared to ask Mrs. Keane outright. Don’t be cheeky, Mrs. Keane would say, cheekiness being classified among the most subversive and therefore the most dangerous crimes among a domestic staff run along strict English lines.

Mrs. Keane would then crinkle her brow in suspicion and take perhaps a closer look at Olive’s well-tended face and soft hands, her careful voice and quick eyes, and that was the last thing Olive needed.

So the lock remained on its guard, and the row of identical little rooms on the sixth floor of the Pratt mansion on Sixty-ninth Street remained about as pregnable to the base male appetite as Miss Ellis’s Academy for Young Ladies, where Olive had been sent for her education, in a lifetime lived long ago. Then as now, Olive spent those dark hours between lockdown and sleep plotting her escape, like a cat brooding in a window. She counted the minutes that passed since the careful click of Mrs. Keane’s shoes had receded down the stairs and out of hearing. She listened to the creak of bedsprings as her fellow housemaids tossed themselves to sleep. She fought the inevitable tide of languor that stole over her like a kind of drunkenness—yes, that was it!—she was plain stone drunk on the long day’s labor, scrubbing and polishing and making beds and fetching, fetching, fetching, on the double, up and down the enormous marble staircase that wound past seven floors to the stained glass dome at the top of the mansion. The temptation of sleep was like the temptation of oxygen.

So tempting, in fact, that she had given in the previous four nights. She had woken up bemused and defeated to the unlocking of the vestibule door and the brisk summons from Mrs. Keane.

Olive slid one hand across her body, under the blanket, and pinched her opposite arm, from shoulder to elbow, until the tears started out from her eyes and her mind sprang into a fragile alertness.

The bedsprings were quiet now. The house was quiet, so quiet Olive could now pick out the few outside noises: the hum of a gentle rain against the glass dome, a distant argument in someone’s garden. The Pratt mansion stood in a quiet residential street, far from the hurly-burly of downtown, but there seemed to be more noise every day, more commerce, and if Olive lay absolutely still, she could feel the creep of the metropolis reaching the Pratt doorstep, reaching rapaciously all the way to the tip of Manhattan island and beyond. New York was a boomtown, New York was where everybody lived or wanted to live, and its lust for fashionable new buildings—unlike the base male appetites—couldn’t be contained by any old lock on a vestibule door. Already more superb houses were rising around the Pratt mansion, which itself was only a year old, and which stood on land that had formed part of James Lenox’s farm only a decade or so before that. Poor Mr. Lenox: Even before he sold his land in building lots, it had appeared on maps with the proposed grid of streets overlaid eagerly on its hilly fields, a foregone conclusion, the ambitious blueprint for a Manhattan paved over in orderly rectangles of houses and shops.

It was a good time to be a builder in Manhattan. It was a good time to be an architect, or so Olive’s father had believed, in that lifetime ago. A year ago.

Many minutes had now passed since the last bedspring had squeaked, since the last pipe had trickled and groaned. The floorboards were still too new to creak. Olive pinched herself again, waited another five minutes, and rose so carefully from her bed that she didn’t disturb a single spring.

Her flannel dressing gown lay over the wooden chair. She slid her feet into her slippers and eased the robe over her shoulders and arms.

Mrs. Keane was right: The Pratt family housemaids weren’t locked in. Olive’s own father had, toward the dusty end of construction, insisted that the newly hung vestibule door should operate a deadbolt from the inside, because my God! Think of the plight of the poor housemaids if, heaven forbid, a fire should tear through the house in the middle of the night! The scandal would be enormous, the headlines thick and torrid and accusatory. They would brand Mr. Henry August Pratt a heartless slayer of the innocent lower classes, a Dickensian villain of the worst sort: in short, a real prat. Possibly he might face criminal charges. So, thanks to her father’s indignant intervention, the deadbolt lifted and the new brass knob turned easily under Olive’s hand, and before she closed the door again she slid her Bible into the crack between portal and frame, a trick she’d learned at Miss Ellis’s.

Outside the housemaids’ corridor, the air was almost fresh. The grand staircase, winding like a great marble ribbon up the center of the house, had been built not so much for ornamentation, Olive’s father had told her, running his finger along the neat architectural drawings before them, though ornamentation—eye-watering, breath-snatching, jaw-weakening—drove Mr. Pratt’s approval of the design. That thick vertical column of empty space, soaring into the dome, created a vital circulation of healthful air. No cramped and stuffy corridors, no atmosphere allowed to fester in place. In the summer, when the vents were opened and the rising hot molecules were allowed to escape harmlessly into the Manhattan sky, why, you might almost call it bearable. You might not even want to flee to your cottage in Newport or East Hampton or Rumson.

But that, reflected Olive, as she turned the corner and found the back staircase with her foot, just in time to avoid tumbling down it, had been her father’s problem all along. He hadn’t understood that, to men like Mr. Pratt, the healthful aspects of his beautiful soaring staircase didn’t matter. It didn’t matter that Mr. Pratt and his wife and children could stay in Manhattan in the summer, instead of spending money on an entirely different mansion in an entirely different town. The point was to show off, to demonstrate to your wealthy friends that—oh, yes—you could afford the finest, too. Even if you couldn’t, really, or wouldn’t. Even if you refused payment to your architect, after taking up two years of his undivided professional time, just because you could. Just because you’d been clever enough to seal your contract on a handshake and nothing else. A gentleman’s agreement.

Now, that was a laugh, Olive thought. Mr. Henry August Pratt, a gentleman.

The lights were out, and Olive didn’t dare light the candle she held in her left hand as she navigated the narrow little staircase, the poor cousin of the one so impressively occupying the center of the house. No, this was Olive’s staircase, the service stairs, plain and honest, her new lot in life, and anyway it got her where she wanted to go, didn’t it? Utility, that was the point. She could slip through quite unnoticed this way, without making any noise, without stirring the tremendous column of healthful air that fed into all the principal rooms of the Pratt mansion. She could enter Mr. Henry August Pratt’s august library without anyone knowing at all.

Still, her pulse slammed against her throat as she pushed open the heavy door. She felt like a thief, even though she knew she was right. She was only correcting a great wrong; she was fighting for her father’s justice, since he could no longer fight for himself. The real thief, she told herself, as her shaking fingers found the small box of safety matches in the pocket of her dressing gown, as she tried and failed to strike one alight against the edge of the box, was Mr. Pratt.

At last the tip of the match burst into light. The crisp sound of the flare, the acrid saltpeter scent, struck Olive’s senses so forcibly that she nearly gasped, certain that everyone in the house would hear and smell them, too. Her blood felt like ice as it pumped along the arteries of her body, down her limbs, up to her head, making her dizzy. My God, she was actually here. Actually standing here in Mr. Pratt’s library, five feet away from his massive desk, holding a guilty candle in the middle of the night.

She had better get to it, hadn’t she?

But where did one begin to find written evidence of a professional relationship that had never been properly formalized? Just send me the bill, Mr. Pratt had said indulgently, and her father had sent the bill, and it hadn’t been paid. Had Mr. Pratt saved that bill? And if he had, was it proof enough that her father had been cheated of his rightful fees?

That Mr. Pratt had, by cheating her father, effectively destroyed his career, because who would employ an architect who gave such unsatisfactory service that his client wouldn’t pay the bill? And who would employ an architect who dared to make any trouble about those unpaid bills?

That Mr. Pratt had, by destroying his career, effectively destroyed his life, because if her father wasn’t an architect, he was nothing, a negation, an invisible column of empty space for whom no one was willing to pay?

Olive realized she was trembling, that the match had nearly gone out. She whipped the candle under the flame. The wick caught instantly, and she dropped the match into the rug just as it singed her fingers.

She held still for a moment, while the taper flickered uncertainly in her hand. The room looked different by night, forbidding, almost Gothic in the ominous dim wavering of the candle flame. There were the bookcases she had polished so industriously that afternoon; there were the deep armchairs and the leather Chesterfield sofa near the fireplace. There was the liquor cabinet, the enormous sash windows now enclosed by damask curtains, the paneled walls, and the long-necked brass floor lamps, one poised next to each armchair.

And the desk.

Of course, the huge brown desk, supported by curved legs and feet in the shape of lions’ paws, covered by a red baize blotter and a small Chinese lamp and a sleek black enamel fountain pen perched in its sleek black enamel holder at the very top and center.

Olive picked up the spent match, placed it in the pocket of her dressing gown, and stepped carefully across the rug and around the corner of the desk, where the drawers lined up on either side of an immense leather chair. (Mr. Pratt was a large man to begin with, six feet tall and framed like a Cossack, and he had allowed a layer of prosperous fat to gather and thicken over that frame, steeped with smoke from the finest imported cigars, so that Olive imagined if he were slaughtered and brought to market, he would taste exactly like a well-cured side of bacon.) The chair was too large to fit between the drawers, so Olive had to pull it away. The wheels squeaked softly, and she froze for an instant, horrified, waiting for doors to bang and footsteps to drum along the stairs. Sleepwalk? She would pretend to be sleepwalking. It might work; you never knew.

But the house remained still. Olive counted the gentle ticks of the clock above the mantel, until her heartbeat slowed to match them. A curious dark spot appeared before the curtains, and another, and she realized she had stopped breathing. A silly thing to do.

She released her lungs and bent down to address the first drawer on the right.

It was locked.

Of course it was locked. My God. What had she been thinking? Even her father had locked up all his papers, and her father’s papers consisted of nothing more than drawings and bills and technical correspondence. She rattled the drawer gently, hoping the lock might somehow wake up and take pity on her, the way one took pity on the beggar children who inhabited the street corners downtown. But of course it didn’t. How stupid. How disastrously stupid, to think she could just steal into Henry Pratt’s library and find incriminating papers, hey presto, lying about unguarded. When even the housemaids’ virtue was kept under lock and key, in the Pratt mansion.

Still she went on staring at the desk drawer, unable to accept her defeat. Just to give up and go back to her bed, after all that effort. To admit that, perhaps, the entire project was beyond her: Olive, reader of books, dreamer of dreams, middle-class daughter of a failed middle-class architect. Absurd, to think that she could carry off a deception like this, a plot for revenge (justice, not revenge, she reminded herself), a clandestine midnight search for papers that, if they did exist, would be hidden well beyond the reach of a common housemaid, even a clever one.

Olive’s hand fell away from the handle of the drawer.

The climb back upstairs was cold and weary. The library lay on the third floor, along with the billiards room at the back (the masculine floor, she called it in her mind); the next floor held Mr. and Mrs. Pratt’s stately bedrooms, and the next held the children’s bedrooms. Well, not children, really. The youngest was Prunella, who was eighteen years old and newly engaged to a wealthy idiot, a widower with a young child; Olive couldn’t remember his name. Then there were the twin boys, August and Harry, who had just returned home from Harvard for the Christmas holiday. It was their last year of university, and everybody was speculating what they would do next: the family home or bachelor apartments? Professional ambitions? Wedding bells? Olive hadn’t listened much. One of them was supposed to be quite wild and artistic; the other was supposed to be simply wild. They had got into daily scrapes when they were younger, said one of the maids, who had been with the Pratts at their old house on Fifty-seventh Street. One of them had gotten some poor woman with child—so it was rumored, anyway—a shopgirl of some kind; Mr. Pratt had dealt with the matter himself, so Mrs. Pratt wouldn’t be bothered.

Olive paused with her foot on the final step at the sixth-floor landing. Now, that might serve Mr. Pratt right. If the story was true, of course, and if it reached the newspapers . . .

A soft sound reached her ears.

Olive glanced down the stairwell and saw a faint triangle of light on the floor below.

She bolted without thinking, right past the entry to the sixth floor and up the last narrow flight to the seventh floor. A storeroom, wasn’t it? She’d never been there. But she couldn’t go to her room; the intruder would hear her opening the vestibule door, would hear her creeping down the corridor to her own room.

But no one would be going as high as the seventh-floor stairs.

She waited in the shadows of the landing. There was no door here; the stairs opened right out to a short hallway. A small round window let in a hint of moonlight, illuminating a narrow door at the end of the hall, six or seven feet away.

A voice called out in a low, rumbling whisper.

“Is someone there?”

Olive took a single step back, toward the narrow door.

“Hello?” the voice whispered again. Not a threatening whisper at all; only curious. Curious and quite male, she thought. There was no doubt of that. The whisper had resonance; it had timbre; it matched, somehow, the expansive, backslapping voices she’d overheard a few hours ago, when the boys had arrived home together in a cab from the station.

He’s sneaking out, she thought. Sneaking out to see a shopgirl, perhaps, or to meet his friends for God knew what mischief.

Olive stood quietly, hardly breathing, while her heart smacked and smacked against the wall of her chest.

Then footsteps, careful and quiet and heavy. Making their way not down toward the first floor, Olive realized in horror, as the tread became louder, but up. Up toward the seventh floor, and Olive’s helpless and guilty body on the landing.

She took another silent step back, and another. The door was at her shoulders now.

A shadow lifted itself up the final steps and came to rest on the landing. Olive could see a large hand on the newel post, a large frame blocking the moonlight from the small round window.

“Hello there,” said the voice, surprisingly gentle. “Who the devil are you?”

“I’m Olive,” she whispered. “The new housemaid. I—I couldn’t sleep.”

“Ah, of course. I couldn’t sleep, either.”

Olive fingered her dressing gown.

A hand extended toward her. “I’m Harry Pratt. The younger son, by about twelve minutes.”

Olive, not knowing what else to do, reached out and took the offered hand and gave it a too-brisk shake. His palm was warm and dry and quite large, swallowing hers in a single gulp, and he smelled very faintly of tobacco. She whispered, without thinking, “Are you the wild one or the artistic one?”

The outline of his face adjusted, as if he were smiling. “Both, I expect.”

“Well. It’s—It’s a pleasure to meet you, Mr. Pratt.”

“Just Harry. Have you been having a look in there?” He nodded to the door behind her.

She hesitated. What else could she say? “Yes.”

“What do you think?”

“Of what?”

“Of my paintings, of course.”

“I—I don’t know. I couldn’t see much.” She raised the last word upward, like a question.

“You didn’t turn the light on?”

“No.”

The young man took a single step forward, and good Lord, just like that, the moonlight from the window poured in around them, and Olive lost her breath.

Harry Pratt was the handsomest man she had ever seen.

She thrust her hand behind her back and braced it against the door.

“Don’t be afraid,” he said softly. “I’m not going to tell anyone.”

“Y—you’re not?” She was stammering like a schoolgirl, utterly unnerved by the angle of his cheekbones, drenched in moonlight. It was unfair, she thought, the effect of unexpected beauty on a sensible mind. (Olive had always prided herself on her sensible mind.) He was Henry Pratt’s son; he was probably a reprobate, a complete ass, undeserving in every way, no doubt just chock-full of those base male appetites that had to be locked up every night by Mrs. Keane. And yet Olive stammered for him. That was biology for you.

Harry Pratt was tilting his head as he stared at her. “No,” he said, a little absent, and Olive had to think back and remember what question he was answering. He tilted his head the other way, and then he moved to her side and peered, eyes narrowed, muttering to himself, as if she were a specimen brought up for his inspection.

“What’s wrong?” Olive whispered.

“I need you,” said Harry Pratt, and he snatched her hand, threw open the narrow door, and pulled her inside.